Architecture is the grandest embodiment of art. Its history is replete with successes and stunning accomplishments. From the awesome Roman Colosseum to the grand romantic gesture that is the Taj Mahal—the engineering, style, art, and scale of structures throughout time are awe-inspiring. Yet, with all the success, there have been some architectural failures as well. Some of these have resulted in human tragedy and, at other times, wasted money and effort. Here, we look at some of the biggest architectural disasters.

The Knickerbocker Theater Roof Collapse, Washington, D.C., January 28, 1922

Blamed on faulty roof construction, the Knickerbocker Theater collapsed shortly after 9:00 p.m. on January 28, 1922, killing 98 people and wounding 133 more. At the time, an intense blizzard lasting more than 24 hours had dumped 26 inches of snow in the nation’s capital. The theater was located at 18th Street and Columbia Road in the Adams Morgan neighborhood.

Various news reports numbered the theater crowd that evening between 300 and 1,000. A silent comedy called Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford was the show. Survivors indicated that there was no advanced warning of the impending disaster. No loud noises, no creaking or leakage. When the roof collapsed suddenly, it fell onto the concrete balcony, which in turn gave way, sending the debris downward to the orchestra section. Moments later, a witness to the incident notified a telephone operator who contacted police, firefighters, hospitals, and the city government office. In response, the city closed all theaters immediately to prevent further fatalities and injuries from collapses.

While people near the scene rushed to help, the effort was disorganized until 600 soldiers and Marines arrived on the scene. Scores of friends and relatives of the patrons showed up as soon as they heard the news. Unfortunately, their attempts to get into the theater hampered rescue efforts. The 26-inch snowfall also delayed many ambulances and other equipment from getting to the scene, but a fleet of ambulances from Walter Reed Medical Center and a few volunteer taxis managed to get through and transport the injured to hospitals.

Even with the large number of rescuers working diligently through the night, they were still unable to remove the debris from the balcony. Police enlisted the help of a young boy to crawl into openings in the rubble, delivering water to victims who were still alive. Houses and stores around the theater were turned into make-shift clinics to help the injured, and a local Christian Science church became a temporary morgue. The severity of the collapse resulted in losses of limbs, forcing amputations to extract some of the survivors. Among the victims were Andrew Barchfeld Jackson, former Congressman from Pennsylvania, and several other prominent politicians, diplomats, and businessmen. One source reported that a violinist in the Theater’s orchestra, who married only 5 days prior, also died in the collapse.

Knickerbocker Theater, National Photo Company Collection [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Several investigations occurred afterward by the city government, both houses of Congress, the coroner’s office and the courts. Some witnesses recalled hearing theater employees discussing whether to remove snow from the roof but deciding that was unnecessary. At any rate, the investigations concluded that the likely cause of the collapse was faulty design—in particular, the use of arch girders rather than stone pillars to support the roof. Despite these findings, courts dismissed the numerous lawsuits filed as a result of the disaster because they were unable to determine who was liable. The theater was rebuilt the following year and named the Ambassador Theater. It remained in the same location until urban renewal in the 1960s tore it down. A bank occupies the site today.

The disaster would claim two more victims years later. The architect, Reginald Geare, whose career ended after the collapse, committed suicide in 1927. The theater owner, Henry Crandall, took his own life 10 years later. He left a note asking reporters not to be too hard on him.

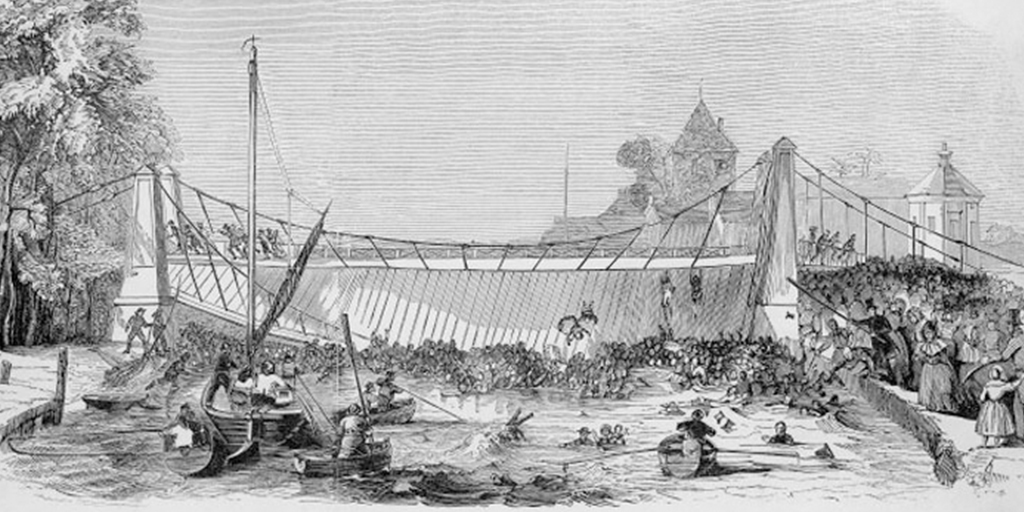

The Yarmouth Bridge Collapse, Norfolk, UK, May 2, 1845

A widely-advertised publicity stunt was the impetus for the tragic Yarmouth Bridge disaster. On May 2, 1845, hundreds of people traveled to witness Nelson the Clown, a performer with William Cooke’s Circus, being pulled along the River Bure by a flock of geese. As Nelson drew near to his destination (the suspension bridge at Yarmouth), hundreds of people rushed onto the bridge to get a better vantage point.

One of the rods supporting the bridge gave way. Though there was an immediate cry from those who noticed the broken rod, it was too late to allow spectators time to escape off the bridge. The chains supporting one side of the structure snapped, catapulting hundreds of people into the river. Bystanders tried to help get people to shore. Doctors and nurses in the town responded quickly, and houses on either side of the river were used to treat the victims and house the dead who had drowned or been crushed by falling bodies and debris.

The extent of the calamity became known that evening when many rescuers pulled bodies from the river. In all, 79 people died, 58 of whom were aged 16 or under. The oldest victim was 64, and the youngest 2. An article in the Norwich Mercury of May 10, 1845, noted that, “In every street are to be seen one or more bodies extended on biers, returning to that home from which but short minutes before they had passed in health and life. The consternation – the agony of the town is not to be described – it is as if some dread punishment was felt to have fallen upon its inhabitants – every face is horror stricken – every eye is dim.”

At the request of the Secretary of State for the Home Department, James Walker, a civil engineer and President of the Institution of Civil Engineers, conducted an investigation of the collapse. Walker determined that both a weld on the rod and the iron used in the construction of the bridge caused it to give way. He also noted that the designers should have contemplated a greater weight tolerance in the construction and should have used more than 2 bars on each side of the bridge to support an additional load.

The Rana Plaza Building Collapse, Dhaka, Bangladesh, April 24, 2013

An eight-story garment factory building outside the Bangladesh capital of Dhaka, known as Rana Plaza, collapsed on April 24, 2013, killing 1,135 people and injuring 2,500 others. Over half the fatalities were women and children (the children were in the building’s day care facilities). The Rana Plaza incident is the deadliest structural accident and factory mishap in modern history.

The plaza housed five garment factories, about 5,000 people, a bank and several shops. The garment factories produced clothing for several brands including, Benetton, Bonmarche, the Children’s Place, El Corte Ingles, Joe Fresh, Primark among several others. The bank and shops closed immediately after several cracks in the building were discovered the day before the collapse. However, the building owners ignored the warnings to abandon the building, and the garment companies ordered workers back to work the next day.

On the morning of April 24, there was a power outage. In response, workers started diesel generators on the top floor. Shortly thereafter, at 8:57 a.m., the top four floors collapsed leaving only the ground floor intact. The Bangladesh Garments Manufacturers and Exporters Association confirmed that 3,122 workers were in the building when it fell. One witness likened the scene to the aftermath of an earthquake.

Though the United Nations had undertaken an assessment of the country’s ability to respond to the disaster, and offered assistance when it determined that Bangladesh was not equipped to handle a catastrophe of this magnitude, the government refused U.N. assistance. Many of the local rescue workers wore “street clothes” and sandals instead of protective clothing. Four days after the collapse a fire broke out at the site, which delayed the rescue effort. Some buried in the rubble resorted to drinking their own urine to survive. The last survivor was pulled from the rubble unhurt 17 days after the collapse.

The report of investigators determined that four factors caused the disaster. First, the plaza was built on a filled-in pond, which compromised its integrity. Second, the building was inappropriately converted from commercial use to industrial. Third was the construction of three additional floors above the permitted height. Lastly, the use of substandard building material could not withstand the vibrations and weight of the generators. Other experts speculated about the decision by factory managers to get workers back into the building to finish orders on time. The demand for low-cost clothing production by clothing brands became another causal factor. Others blame the trade unions that could have put more pressure on management to ensure safer working conditions.

The Rana Plaza Building Collapse, Dhaka, Bangladesh by rijans [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The day after the collapse, Dhaka capital development authorities filed suit against the owners of the factories. Soon thereafter, the Prime Minister called for the arrest of the building owner and the owners of the garment factories on criminal charges. Two days after the incident, garment workers in the area rioted, targeting vehicles, commercial buildings and garment factories. Another large protest occurred on May 1 (International Workers’ Day). When the government announced that it would pay the impacted garment workers their outstanding April salaries plus three months of additional pay, workers ended their protest. In 2016, 38 people were charged with murder in connection with the collapse, and another three people with aiding the building owner in his unsuccessful attempt to flee the country.

The impact of the tragedy on Bangladesh’s huge garment industry (accounting for 12% of the country’s GDP and employing four million people) was significant. Labor reforms concerning worker pay and factory safety compliance in Bangladesh were put into place. Two major agreements between global retailers, brands and trade unions were signed. In addition, the Apparel and Footwear Supply Chain Transparency Pledge emerged from a coalition including, the Human Rights Watch, the International Labor Rights Forum, and the International Trade Union Confederation, among others. The Pledge requires companies to disclose all sites that manufacture their products with addresses, types of products and number of workers at each site. Yet, the Human Rights Watch found that by the end of 2017, only 17 of 72 apparel companies agreed to implement a transparency pledge. Clearly, more work needs to be done.

Kangbashi District, Ordos City, China

In 2004, the Chinese government, to increase its GDP, built the Kangbashi District about 18 miles outside the city limits of Ordos City (population two million). The government poured hundreds of millions of dollars into roads and houses to accommodate an estimated one million residents. Though most dwellings sold, a majority were purchased by financiers as investments. The result was something akin to a frontier ghost town.

Investment options in China are very limited. Thus, real estate is one of the few alternatives where people can store their excess wealth. This was certainly the case in Ordos where many people became instantly rich during the coal boom. People bought dwellings with the intention of living there later in life or gifting a house there to their children upon marriage.

During the first five years of its construction, Kangbashi had a complete downtown area with a museum, opera house, library, commercial space, and government offices. Schools and hospitals followed a few years later. Because of the delay in building communal facilities, though, many who worked in Kangbashi commuted there from Dongsheng. Another factor contributing to its ghost town appearance relates to a common building practice in China where homes are pre-sold, sometimes years before the dwelling is ready for occupancy (even though from the outside they appear habitable). While many investors bought homes in Kangbashi, there is reluctance to sell because the prices are so low due to oversupply.

Ordos.Kang Bashi.Ordos library by Popolon [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

The government touts that progress is being made, yet Kangbashi has only 100,000 residents today, a far cry from the anticipated one million. The facts are undeniable: the design incorporating vast public spaces and large distances between streets and basic services does not comport with the advertising pitch of Ordos as being a walkable city.

Olympic Stadia, Athens, Greece

Olympic Stadia, Athens, GreeceMister No[CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]

Greece spent $11 billion dollars on a dozen venues for the 2004 Olympics (double the country’s budget for the event). These stadia included more than a dozen separate venues for events like judo, field hockey and table tennis. After the Olympics, more than half of the stadia were abandoned. Little or no thought went into planning for reuse after the games. Many experts speculate that the 2004 Olympic spending played a major part in the financial crisis that still plagues Greece today.

As we move into the future, we are wise to consider the past, remembering both the architectural triumphs through the ages, as well as the failures.